ADMIRAL HALLIFAX AND THE LODESTAR ACCIDENT: 80 YEARS AGO

Commander Leon Steyn, Curator SA Naval Museum

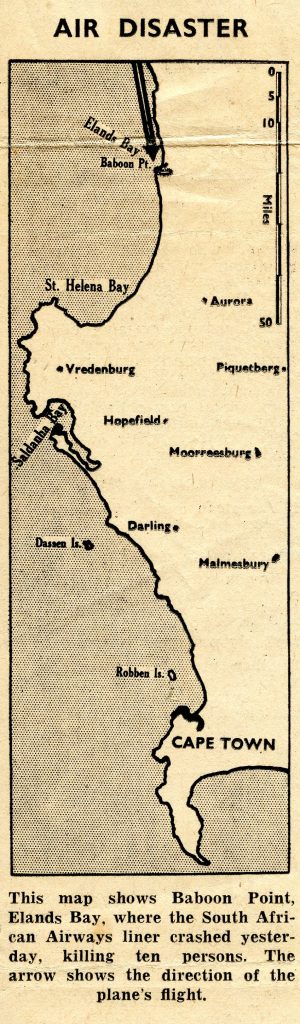

On 28 March 2021 the SA Naval Museum, in association with the Naval Heritage Trust commemorated the passing of the first director of the Seaward Defence Force – the forerunner of the modern day South African Navy – Rear Admiral G.W. Hallifax CMG. A South African Airways (SAA) Lockheed Lodestar aircraft that carried him and five other passengers on a flight from Windhoek to Cape Town, flew into high ground near Baboon Point close to Elands Bay on 28 March 1941, with total loss of life.

HALLIFAX AND THE SEAWARD DEFENCE FORCE

At the outbreak of the Second World War on 6 September 1939, the Union Defence Force found itself woefully unprepared and without a naval force of its own. The country was still dependent on its ‘big brother’, the Royal Navy, who had maintained its naval presence on the high seas ànd in Simon’s Town by virtue of its African and South Atlantic Station there. But the Union government was eager to establish its own seaward defence force that could undertake the responsibility for the defence of South African ports and home waters. The war had quickly gained momentum and in the South Atlantic the activities of German raiders and the pocket battleship Graf Spee raised serious concerns. Some form of local seaward defence had to be organised – built up from scratch – and as a result General Jan Smuts approached an experienced, retired Royal Navy Officer to become the director of a newly constituted Active Citizen Force unit, the Seaward Defence Force.[1]

Guy Waterhouse Hallifax was born at Southampton on 21 June 1884. He was the oldest of three sons, two of whom served in the Royal Navy. His father was Rear Admiral John Salwey Hallifax (9 March 1846 – 11 December 1904) and his mother – Charlotte Annie – was the daughter of Major General Thomas de Courcy Hamilton VC (20 July 1825 – 3 March 1908). Guy enlisted at the age of 15 and spent the first year of his service on the cadet training ship HMS Britannia (1899). Prior to the First World War he served as Naval Advisor in Turkey and in 1914 received the Order of the Medjidieh (3rd Class) for his services there. Hallifax then served on the dreadnought battleship HMS Ajax for the duration of the First World War and was present at the Battle of Jutland. He was made a Commander of the Order of St Maurice and St Lazarus (Italy) in 1918. After the war he was sent to South Africa to conduct an inspection of wireless stations in the Union, a visit that probably prompted his return to the country, following his retirement many years later. He served on another battleship HMS Valiant (1921) and attended various disarmament meetings at Geneva during this time. In 1924 he was promoted to the rank of Captain and took command of the light cruiser HMS Carlisle attached to the China Squadron, from 1926 to 1928. Appointments as Naval Attaché in Paris, Madrid, Brussels and The Hague followed. He returned to active duty for another command at sea in 1932, this time as the Officer Commanding of the battleship HMS Malaya. In 1935 he was appointed Director of the Signal Division of the Admiralty and was promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral, but retired, in the same year. Following his retirement Rear Admiral Hallifax left for South Africa as secretary to Lord Clarendon, who was then the Governor-General in South Africa in 1936. He continued in this capacity for the first four months of the governor-generalship of Sir Patrick Duncan. He stayed on in Cape Town in retirement, until he was approached by Smuts to take up the directorship of the newly formed SDF.[2]

The SDF was constituted on 9 October 1939 and Hallifax’s first important task was to acquire ships and to train sailors in quick time. The Royal Navy assisted and released a number of retired RN personnel, resident in South Africa, while members of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve in South Africa (RNVR SA) were made available to the SDF. Only five members of the original (but failed) SA Naval Service (established in 1922) had remained in permanent service and these members were also transferred to the SDF, while the recruitment of full time volunteers started in all earnest.[3]

THE WALVIS BAY DETACHMENT

To assume the responsibilities for minesweeping duties and anti-submarine patrols in the approaches to South African ports, seventeen commercial whalers and trawlers were requisitioned and converted for war service. Additionally the SDF took over control of the port war signal stations and merchant shipping examination services at Cape Town, Durban, East London and Port Elizabeth. When the SDF formally came into existence on 15 January 1940, it comprised fifteen minesweepers and two examination vessels that were manned by seventy-four officers and 358 ratings. By October 1940 Hallifax had managed to expand the SDF to twenty-four minesweepers and eight anti-submarine whalers while the personnel compliment had grown to 183 officers and 1 049 ratings. At the request of the Admiralty a flotilla of anti-submarine vessels were made available for service in the Mediterranean and the first of these arrived in Alexandria in January 1941.[4]

A detachment of the SDF was established in Walvis Bay in January 1941, even though the War Plan had originally not included it as a defended port. The RN Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic, had however requested Walvis Bay to be made available as a bunkering point for merchant ships as an alternate to the busy port of Freetown. Arrangements had to be made for the handling of ships there. The tender HMSAS Clara was sent from Cape Town and the minesweeping vessels HMSAS Aristea and HMSAS Goulding followed soon thereafter and began routine sweeping of the bay. As part of the harbour defences there, the 7th Heavy Battery of the South African Artillery had been established on 1 September 1939, initially with 60-pounder medium artillery field guns. These were later replaced by two 12-pounders and two 6-inch guns on fixed mountings.[5]

Facilities at the isolated harbour town of Walvis Bay were lacking and arrangements had to be made to remedy certain shortcomings. The SDF had to share the rudimentary facilities with the 7th Heavy Battery of the SA Artillery. The Commanding Officer of the Walvis Bay Detachment, Lieutenant Commander Shannon reported, among others that;

Food at a place like this, where there is nothing much to do besides work, eat and sleep, assumes an importance which is perhaps out of proportion. Unfortunately, however, it has to be dealt with in regard to its importance. The food, as supplied by the battery, is reported to Me by many of the ratings, to be very bad and badly served. This is a very delicate situation, as I am unable to tell the Battery Commander of the big difference between Naval and Army rations, but I have approached him gently. He tells me, after investigation, that he can find no Reason for [my] complaint [….]. The worst punishment I can inflict on any of the ratings from the ships is to bring them ashore and make them feed at the Battery. The only solution that I can see is for the SDF to have their own mess in the proposed accommodation.[6]

It was around these preparations and proposals that Admiral Hallifax visited the detachment in Walvis Bay. During the week of 24 March 1941 he flew from Cape Town to Walvis Bay for the inspection and was accompanied by Colonel Harold E. Cilliers who was the director of the coastal anti-aircraft and artillery forces and Lieutenant Colonel Gordon P. Shearer, the deputy director of technical services in the UDF. [7]

THE ILL FATED FLIGHT

To travel from Cape Town to the distant and desolate Walvis Bay, a South African Air Force De Havilland Dragonfly was placed at their disposal. This was a twin-engine civilian luxury touring biplane that could carry a maximum of four passengers and was impressed into South African Air Force service just a year earlier, in March 1940. The flight from Cape Town[8] to Walvis Bay must have been uncomfortably long and stressful as the Dragonfly – piloted by Lieutenant M.J. Mitchell – developed intermittent engine problems on the way to Walvis Bay. This left the senior officers with some reservation about its reliability. Lt Mitchell therefore ferried the Dragonfly back to Wingfield, while Hallifax; at the conclusion of the inspection; opted to return to Cape Town on the scheduled South African Airways flight from Windhoek. [9]

Hallifax, Cilliers and Shearer boarded the SAA Lockheed Lodestar at Windhoek on Friday morning 28 March 1941, joining three civilian passengers on the flight. They were Mr Charles Patrick McMichael (47) of Muizenberg who was the district manager of Dunlop South Africa in Cape Town, Mr Morris Kaplan (48) a general merchant from Windhoek and Mr Alexandre Kendierski [10] (33), a pelt buyer from Windhoek.

Admiral Halifax and his passengers must have been pleased to return to Cape Town in the much larger, faster and more comfortable Lockheed Lodestar. In fact, the particular aircraft (registration ZS-AST) was brand-new and delivered to SAA just a few months earlier in December 1940. SAA was an early customer of the new Lodestars and ordered no less than twenty–nine of the type, but when World War 2 broke out, these and several other civilian aircraft; were impressed into military service. ZS–AST was however one of the exceptions and retained in SAA service[11] to maintain a selected airline schedule. One of the newly established routes was the so-called ‘Luanda Run’ that connected Portuguese West Africa[12] with the Union of South Africa, with weekly flights between Luanda and Cape Town via Windhoek. [13]

The Lodestar departed Windhoek as scheduled at 08:45 for the estimated three and a half hour flight to Wingfield airfield near Cape Town. The crew flying on that day was the pilot, Captain Fred W. Le Roux (28), first officer (co-pilot) Lieutenant J.P. Meyer (21), together with engineer Air Sergeant John W. Shelly (27) and wireless operator Sergeant Andries P. van Wyk (23). These men were all airways personnel, but were mobilized and transferred to the SAAF when the war broke out and for that reason were accorded military (air force) ranks. Fred Le Roux – a resident of Germiston – had in fact received his initial flying training in the air force before he joined South African Airways in 1938. John Shelly was a member of a well-known Sea Point family and had joined SAA in 1937. One can assume that the crew was relatively inexperienced on this particular type of aircraft, as the new Lodestars had only arrived in the country a few months earlier.

The Lodestar flew a direct route from Windhoek to Cape Town without incident until about two and a half hours into the flight. The crew were concerned about the deteriorating weather ahead. Coastal fog had moved in along the Lambert’s Bay region, which on this day unfortunately extended up to a thick cloud bank which rose ahead of them – well above the normal cruising altitude of the Lodestar – obscuring the terrain below.[14] Le Roux entered cloud without any visible landmarks to verify his position and now had to rely on instrument flying[15]. At 11:21 the communication centre at Wingfield received a message from the Lodestar reporting that they were ‘flying due south in thick mist’. At 11:37 another short message was transmitted – providing their estimated time of arrival at Wingfield as 12:05.[16]

Finding all landmarks obscured Le Roux adopted a procedure, normal for these occasions. This would be to descend below the cloud and mist – but some distance out to sea (to the west in this case) – and to fly back towards the land to follow the coastline to Table Bay to land at Wingfield.

After having been in IMC conditions for about 30 minutes a short message was transmitted to Wingfield at 11:41: “Coast now visible, OK”. The coastline that became visible to Le Roux was in fact just north of Elands Bay – still 120 miles away from Cape Town – where the coast runs north and south. But at Elands Bay itself the coastline turns sharply to the west and consists here of a steep rocky ridge, 638 feet high, running west for some miles to a rocky point known as Baboon Point. Flying at low level in the foggy conditions, the coastline must have been barely visible to Le Roux – but the obstructing Baboon Point was not. At 11:45, the Lodestar crashed into Baboon Point.

In Elands Bay – then only described as – ‘a bleak, wind-swept and sandy village consisting of a post office, a fishery and some houses’, Mr E.B. Smith, who assisted his father in the post office heard the drone of an aeroplane at around 11:45. The drone grew louder and soon Mr Smith – standing outside the post office – saw the machine looming through the mist. It was flying extremely low as it passed over the village in a southerly direction. Soon thereafter they heard a tremendous crash and explosion and realised that the aircraft had just struck the high ridge above the village. Mr Smith immediately ran to the scene of the accident – obscured by the mist – halfway up the ridge. He found the blazing wreckage of the Lodestar, but the intense heat made it impossible to get nearer than 30 feet. Some badly mutilated bodies lay near the inferno. Nothing could be done.

“The fire blazed fiercely for about half-an-hour, when it subsided, but the wreck was still glowing several hours later at 5 p.m. when only the red-hot metal framework remained.”[17]

THE AFTERMATH

A memorial service for the victims was held in the St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town on 3 April and attended by a large and representative congregation. The deceased were all buried in a collective war grave (UL.131) in the Commonwealth War Graves section of the Plumstead cemetery outside Cape Town – their final resting place.[18] See Commonwealth War Graves Plumstead Cemetery

Guy Hallifax left a wife and step-daughter behind. He had married Madeleine Sumner Simms in 1930. His younger brother, Vice Admiral Ronald Hamilton Curzon Hallifax CB, CBE, sadly perished in another air accident. The Royal Air Force Douglas Dakota in which he was flying back to the UK, crashed at Sollum, Egypt on 5 November 1943. His son Admiral Sir David John Hallifax, KCB, KCVO, KB (3 September 1927 – 23 August 1992) carried the family’s proud naval tradition forward into the 1980s.

Rear Admiral G.W. Hallifax: Medals & Awards: Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG), 1914-15 Star, British War Medal, Victory Medal, War Medal (1939-45), Africa Service Medal, King George V Silver Jubilee Medal (1935), King George VI Coronation Medal (1937), Order of the Medjidieh (3rd Class) (Turkey), Commander of the Order of St Maurice and St Lazarus (Italy)

The “Union Airliner Disaster” and death of Admiral Hallifax made front page headlines and came as a huge shock to those in the SDF. Guy Hallifax was highly regarded and respected: “His naval and diplomatic ability, optimism, resourcefulness and fair degree of independence from the apron-strings of Pretoria, enabled him to ensure that the second attempt by South Africa to establish a navy did not fail, and his loss was therefore a blow to the Navy in its early formative years.”[19]

The consequential appointment of Captain (later Commodore) James Dalgleish as director however allowed the important wartime work to continue and to be completed “in a manner which provided the best possible epitaph to his [Hallifax’s] memory.”[20] Dalgleish was a founding member of the SA Naval Service in 1922 and the most senior Permanent Force member in the SDF. He subsequently saw to the amalgamation of the SDF and RNVR (SA) and ensuing establishment of the SA Naval Forces on 1 August 1942 and lead the organisation to the end of the war.[21]

In a sad turn of events, another Lockheed Lodestar accident also took the life of the prominent military commander, Major General Dan Pienaar on 17 December 1942. The Lodestar carrying him and eleven other officers crashed into Lake Victoria, shortly after take-off from Kisumu airport in Kenya. The famed ‘Pienaar of Alamein’ and his fellow officers were returning to the Union at the conclusion of the North African campaign. [22]

A Lockheed Lodestar (ZS-ASM) that was taken into SAA service in December 1940 and impressed into SAAF service shortly thereafter (serial 237). Seen here during the East Africa and Abyssinian campaign of 1940/41 (Photo DoD Archives)

EIGHTY YEARS LATER

On Sunday 28 March 2021, the curator of the SA Naval Museum Commander Leon Steyn and Warrant Officer (Ret) Harry Croome; representing the Naval Heritage Trust; unveiled a small plaque near the crash site, in honour of Admiral Hallifax, the crew and the other passengers that lost their lives in this tragic accident. Few remember the event, but local Elands Bay enthusiasts Mariëtte Louw-Capes and Emré Forster had kept the local memory of Hallifax and the Lodestar accident alive.

The aircraft was destroyed when it impacted the rocky ridge and the post impact fire consumed almost everything else. Larger aluminium pieces of the wreckage that remained – such as the tail plane – were removed by farmers and – as the story goes – later used to construct chicken coops in the village! Even though the aircraft accident occurred more than eighty years ago, small pieces of wreckage can still be found strewn around the crash site on the rocky ridge high above Elands Bay. Mariëtte and Emré’s regular Sunday-hikes up to the site have unearthed an interesting array of artifacts – small but poignant reminders of the accident. Some of these artifacts have been recovered and are now on display at the Naval Museum in Simon’s Town together with other display items related to Admiral Hallifax.

South African Airways continued to operate the Lockheed Lodestar after the war, but retired the last of the twenty-nine Lodestars from service in 1955. Fortunately two of the aircraft have been preserved as static exhibits – for the public to see – one at the SAAF Museum in Pretoria and the other at the SAA Museum at Rand Airport. A handful of Lodestars are still maintained in flying condition by private collectors/museums in the USA.[23] See Flying the Lockheed Lodestar L18 Mid America Flight Museum

For some time now there have been talks about the possible establishment of a local history museum in Elands Bay itself. It is not just the Lodestar incident that features as a part of Elands Bay’s Second World War history, but also the location of a ‘Chain-Oversea-Low-Radar’ station that was constructed against the southern slopes of Baboon Point in November 1943. The technological marvel of radar was still in its infancy; most famously utilised during the Battle of Britain. The radar site at Baboon Point was one of several along the South African coastline to detect enemy raiders and submarines, most notably the German U-boats that posed a real threat to shipping during the war. The site was dismantled in 1954 but the structures of the technical buildings remained largely intact.[24]

The SA Naval Museum and Naval Heritage Trust have pledged their support to both the Western Cape Provincial Museum Service and Cederberg Municipality Tourism office towards the creation of a museum in Elands Bay.

END NOTES

[1] HR Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces during the Second World War: 1939-1945, Simon’s Town, Naval Heritage Trust, 2008, p.17; First offered the post of Deputy Director of Coast Defence and OC SA Naval Service, which he accepted, but legal problems concerning the transfer of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (South Africa) to his command necessitated the establishment of a new Active Citizen Force Unit, the Seaward Defence Force, with Rear Admiral Hallifax as Director. Also see IJ van der Waag, ‘Thin Edge of the Wedge: Anglo-South African relations, dominion nationalism and the formation of the Seward Defence Force in 1939-1940’, Contemporary British History, Vol. 24, No. 4, December 2010, pp.427-449.

[2] Anon. ‘Notable Career of Admiral G.W. Hallifax’, Rand Daily Mail, 29 March 1941, p.11; WM Bisset, ‘Admiral Hallifax Centenary’, Navy News, Vol. 3, No. 7, July 1984, p.6.

[3] Gordon-Cumming op. cit., p.18.

[4] Ibid., p.29.

[5] Ibid., p.173; L Crook, Island at War: 1939-45, Simon’s Town, Naval Heritage Trust, 2013, p.55.

[6] DoD Archives, Seaward Defence, Box 48, File No SD10/5/4/5, ‘South African Naval Forces Progress Reports – Walvis Bay Detachment’, 14 January 1941 – 28 December 1942.

[7] Colonel Harold Ernest Cilliers (40) was the brother of Colonel F. Cilliers, Officer Commanding of the Steel Commando that toured South Africa in 1940 and the son of Captain P.S. Cilliers, Member of Parliament for Hopetown; Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Pitcairn Shearer (33) was an officer in the British Army (Royal Engineers) and posted to the Coast Artillery Brigade in May 1939 to assist with the installation of facilities for the emplacement, mounting and installation of guns. See Anon. ‘Notable Career of Admiral G.W. Hallifax’, Rand Daily Mail, 29 March 1941, p.11; L Crook op. cit., p.31.

[8] Wingfield Aerodrome was established in 1935 as the first Cape Town municipal aerodrome and at the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 transferred to the SAAF, as Air Force Station Wingfield. After the war Wingfield reverted to its commercial use, until 1954 when the new DF Malan Airport (the current Cape Town International Airport) was opened.

[9] G de Vries, Wingfield: a Pictorial History, Cape Town, 1991, pp.154-155.

[10] Several iterations of the surname can be found in contemporary sources. The most common spelling of the surname is however ‘Kindziersky’, a Polish surname which today, is more prevalent in the United States of America.

[11] ZS-AST was never allocated a SAAF serial number.

[12] The latter-day Angola.

[13] Anon. ‘SA Airways Liner Crashes: 10 Dead’, Cape Times, 29 March 1941, p.1. Also see Anon. ‘Union Airliner Disaster’, Cape Argus, 28 March 1941, p.1.

[14] M. Young, A Firm Resolve: a history of SAA accidents 1934 to 1987, Durban, Laminar Publishing, 2007, 43.

[15] Instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) is an aviation flight category that describes weather conditions that require pilots to fly primarily by reference to instruments, and therefore under instrument flight rules (IFR), rather than by outside visual references under visual flight rules (VFR)

[16] de Vries op. cit., 154.

[17] Anon. ‘SA Airways Liner Crashes: 10 Dead’, Cape Times, 29 March 1941, p.1. Also see Anon. ‘Union Airliner Disaster’, Cape Argus, 28 March 1941, p.1.

[18] Anon. ‘Memorial Service’, Cape Argus, 3 April 1941.

[19] CJ Harris, War at Sea: South African Maritime Operations during World War II, Cape Town, Ashanti Publishing, 1991, p.40.

[20] Gordon-Cumming op. cit., 173

[21] Ibid.

[22] Lake Victoria claimed two more SAAF aircraft during the Second World War. A Douglas Dakota (6807) crashed on 11 May 1945 with one casualty and another Dakota (6812) crashed on 11 July 1945 with total loss of life (28 casualties). A contributing cause to the accidents at Kisumu was thought to be the so-called katabatic wind condition that often affected Kisumu airport in the early morning.

[23] ‘Lockheed Lodestar’. Wikipedia. 1 May 2021. <https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_Model_18_Lodestar> Accessed on 1 May 2021.

[24] Peter Brain, South African Radar in World War II, Cape Town, The SSS Radar Book Group, 1993, 51-52.